Beyond The Spotlight: Nickolas Means

Welcome to the latest blog post in the Beyond The Spotlight series. In each post, I interview conference speakers about their talk process, preparation and delivery, showing what happens behind the scenes of great conference talks.

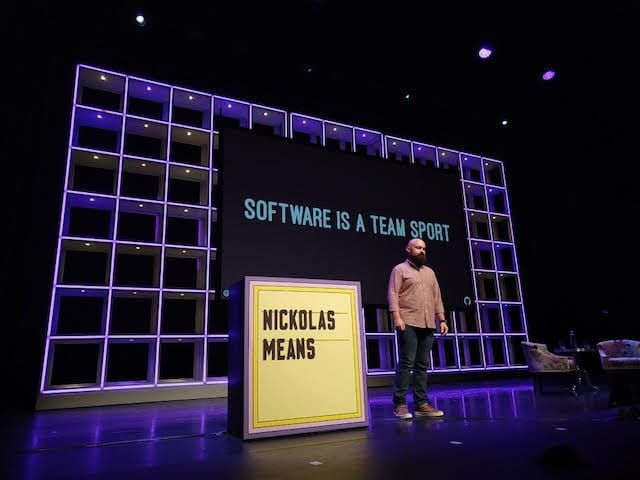

In today’s Beyond The Spotlight, I’m chatting to Nickolas Means. You may know Nickolas from his great storytelling talks about plane crashes, nuclear reactors and other feats of physical engineering history.

Nickolas Means loves nothing more than a story of engineering triumph (except maybe a story of engineering disaster). When he's not stuck in a Wikipedia loop reading about plane crashes, he leads the engineering team at Sym, helping create the building blocks engineering teams need to build delightful security and compliance workflows. He works remotely from Austin, TX, and spends his spare time hanging out with his wife and kids, going for runs, and trying to brew the perfect cup of coffee.

Hi Nickolas! Thanks for taking the time to chat with me today. I’ve always enjoyed your Lead Dev story talks, so I’m excited to hear more about what goes into creating them.

What motivated you to give talks?

Nickolas: It's been a while since I started. I went to a few conferences and I couldn't figure out what to do with myself at a conference. I was just lost. I would go and sit and hear content and come away not feeling like it was a very valuable experience for me. I saw people who were speaking, having a very different experience with me, being engaged in the hallway track, and having good conversations. I'm a pretty deep introvert and have a real loathing for small talk.

So part of my motivation in getting into speaking was to bypass all of that. To be able to go to a conference, get on stage, give a presentation, and then suddenly there's this natural thing for everybody there to talk to me about, so we can just skip the small talk and talk about a thing that I'm very interested in, because I just talked about it for 30 minutes on stage.

Most of the conferences that I've seen you speak at, you end up being the closing keynote speaker. How do you now deal with that? Given that what you enjoy most is being able to talk about the thing you just spoke about.

There's usually some kind of mixer event or whatever after that closing keynote. But also, especially at Lead Dev, there's enough folks that know me now that I can show up and have some of those conversations before I've even gotten on stage and given the presentation.

It's one of those things that you get compounding returns out of speaking as you build a reputation in the communities, more people know who you are. It makes you less of a stranger when you walk into a giant room full of people because there are people there that know who you are.

You know, it's funny, the very first time I spoke, the speaking slot that I got was the very last talk at the end of a three day conference. And so this whole buildup, of knowing it's going to help me not be such an introvert at the conference, didn't play at all that, that first time.

What do you enjoy most about giving a talk?

Now that I've gotten comfortable on stage, and really found my storytelling style, the thing that I enjoy most is watching the audience. I enjoy just seeing the looks on their faces as I take them through a journey from stage.

Because I know what's coming, but the audience doesn't. I know generally when they're going to laugh, I know what's going to be surprising. The buildup to those moments and the anticipation of getting that reaction from the audience is probably my favourite thing.

Let's shift gears a bit to talk about your talk creation process. How do you come up with your talk ideas?

That's an interesting question. You know, it's more a part of who I am than anything. I've always been really curious about the world around me and how it works, especially the mechanical parts of the world around me.

To the point that when I was a kid, my parents bought me this series of books called How Things Work. So that they wouldn't have to answer all of my questions. They would only have to answer some of them.

And I spent hours reading those books, looking at things like, how does an internal combustion engine work? And how is that different from a jet engine? And how does an airplane wing keep an airplane in the air? That sort of thing. Then Wikipedia came along and I could go even further, even faster. I would go on these ADHD fueled binges, just reading Wikipedia articles for hours and hours, just learning about random plane crashes or random things that I wanted to know about.

So most of the things I talk about are things that I've probably read about for years. Once or twice a year, one or two of those ideas bubbles up into something that seems like it's ready for me to create a talk about it, or that I have some idea what application I would want to draw from it.

So that's the next bit that I want to ask about: a good story always seems to be at the heart of all your talks. How do you go about linking that interesting story to the engineering or leadership takeaway? Is that something you find after you've gotten the story that you want to tell or do those go hand in hand?

You know, it's funny. Sometimes I know exactly where I'm going when I start writing a talk and other times I have some vague idea enough to fill out a CFP response, but not an actual direct understanding of where the talk is going to land until I get into it. I usually have a vague sense at least of what lesson I want to draw from it.

Software is a very young discipline: we've been building things out of stone and steel for thousands of years, and there's a lot of lessons there that apply to how we build software. But we're stuck in our silo of thinking that software is this unique, interesting discipline and we don't learn a lot of those lessons.

My focus is trying to find a lesson from the world of physical engineering that I can bring back to software to shortcut some of our learning about how to work together to build great things.

Are there any interesting stories that you want to tell that you haven't been able to link back yet?

There are plenty. I keep a notes file of things that I might eventually want to talk about that I just haven't found the right application for. Air France 447 is a good example. It was the plane that crashed on the way from Rio de Janeiro to Paris, and they literally stalled it all the way into the ocean.

It’s a fascinating story that gets into how humans interface with machines. There's definitely something interesting there, but I'm not quite sure how to do a talk around a story where everybody dies. I'm not sure how to bring something redemptive out of that story. So I haven't tried it yet.

Once you have your idea, your story, what's next for you? How does your talk creation process look like?

A lot of times I will have read ambiently about something for years, and then I read very intensely about it in the months before I start building a talk on it. So I'll read two or three books often, and try to come up with a version of the story that I have confidence is true and accurate.

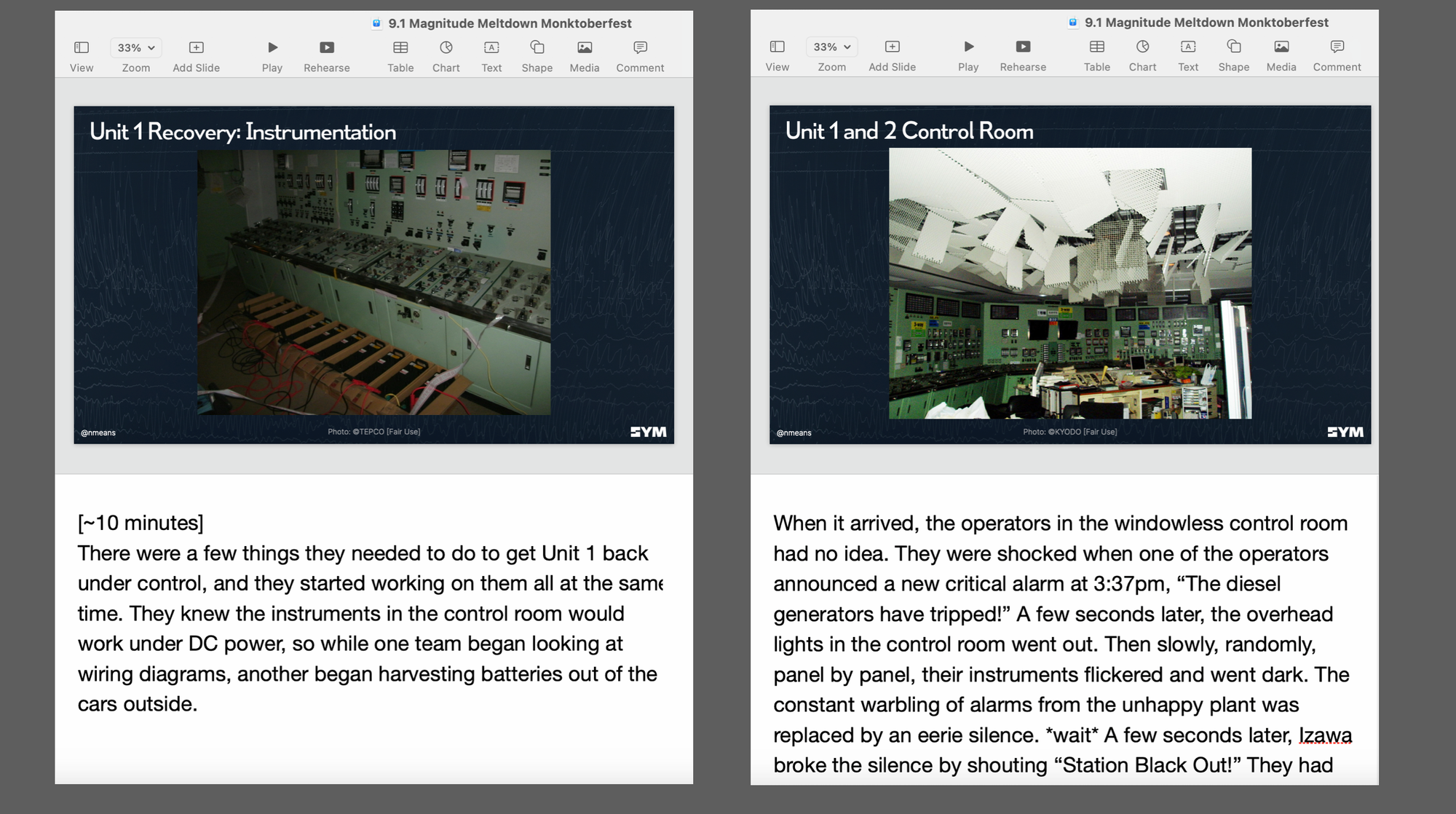

You get into things like nuclear reactor disasters and there's so many different versions of how things went down that part of the editorial process before I ever start putting a deck together is figuring out what is the version of the truth that I want to get on stage and tell and that I have confidence is accurate.

Once I've got the story arc and I know kind of where I want to go, a lot of it's informed by what visuals I can find to go in the deck. So when I sit down and actually start writing the story there are times where I think I know where the story arc is going and I have to back out, because I can't find visuals to fit that part of the story arc. And I have to find a different way to tell that part of the story.

During this process, how do you keep track of that story arc? Does it all live just in your head or do you write it down as an outline or post it notes?

By the time I've read as much as I can about these topics, most of it's in my head. I know the story pretty well at that point. I then dive straight into the slide deck and just build the deck.

I've gotten better at this over the years. When I first started doing these storytelling style talks, I would end up with 60, 75 minutes of material for a 30 minute talk slot. Which I had built into the slide deck. I would then have to go through and verbally edit my way through and trim it down.

I'm better at knowing what I can fit in a 30 minute talk now. Although if you talk to Meri Williams at Lead Dev, it's always 35 minutes. I'm always five minutes long. Cause I can't quite leave all of those darlings on the cutting room floor.

So how long generally does it take for you to put a talk like that together?

The research takes a long time, obviously. However long it takes me to read a few books. But then the actual talk itself generally comes together over the course of a week, maybe two weeks. So once I get to the point that I'm sitting down and actually building something in Keynote, it all comes together really quick because I have a pretty good idea of where I want to go.

And then, here's some discovery that happens as I work my way through the narrative arc. There's some changes that happen through that process. Sometimes the conclusion changes as I work my way through how I'm telling the story. I see an angle that I didn't see before as I actually put pen to paper and try to figure out how to tell the story.

But generally it takes me a week or two to write it and then probably another week to work my way through talking through the talk multiple times. Figuring out where the rough spots are, figuring out where the story doesn't flow as well as I would like it to, and getting that final bit of polish on it.

You mentioned “Talking through your talk”: how do you do that? How do you do those practise runs? Is that just on your own? Is that with people?

Generally it's on my own. There are a couple of times when I've had either smaller conferences or groups of friends that I've given a talk to, before I've gotten on a big stage and given it.

But most of my practice runs are literally just editing passes. One thing I've learned about myself is I am a much more effective verbal editor than if I sit down and try to edit the actual text on the page. So I will find hiccups. I will find places that I don't think the talk connects very well. I will find rough transitions between slides as I talk through them, that I would never spot if I just sat down and read the deck.

How do you get the timing of your talks right?

I tend to signpost my way. In my speaker notes, I'll generally put timings along the way that I should be to this point at 10 minutes in or I should be to this point at 15 minutes in.

That gives me a signal if I should be speeding up or slowing down where I am. Generally by the time I get on stage to deliver it, I've been through it enough times that know what pace I need to hit in order to get it right on stage. It still takes me a lot of discipline to slow down when I actually get on stage and give the talk because there's still that nerves driven urge to speed up.

And my talks are generally a little bit too long for the time slot anyway. But the flip side of it, the style of storytelling that I try to do involves a lot of deliberate speaking, a lot of slowing down on key points, and a lot of deliberate pauses. I have to leave myself time to be able to do that.

It does take a lot of deliberate attention to timing.

So let's talk about that: the delivery of your talk. You've touched on things like deliberately slowing down. How do you plan for that?

It's all in my speaker notes.

When I first started speaking, I had this idea that to be a real speaker, I had to speak from an outline. The thing that I quickly learned is that when I was fresh off of my research, when I had just done all of the reading and I had just put a talk together, I can speak very effectively off of an outline.

It definitely sounds super engaging, super off the cuff, that sort of conversational style that I go for. But when I would go to give the presentation a second time, three or four months later, I wouldn't remember any of that stuff. And I would be missing key details in the outline. So over the years, I've shifted to being completely manuscripted.

If you look through my speaker notes, I'll have cues in there for when I need to click my remote to trigger an animation. I'll have deliberate pauses baked in. And I'll have those timings baked in so that I can make sure that I'm hitting my cues as I work my way through the talk.

That sounds very similar to my own approach! Looking at the day of a presentation, what do you do to prepare on the day? Do you have any habits or rituals that you do?

Room service breakfast. That is my favourite speaking treat that I give myself every time I get on stage to speak.

Usually there's some last minute prep that I'm doing. Usually I'm a little bit frantic in the morning when I'm getting on stage to give a presentation. And that just sort of is a nice way to start the day: somebody else is taking care of my breakfast. They're bringing it to my hotel room so I don't have to be ready by any certain time in order to get out of the room to go get breakfast. It calms me and sets this mode of calm for the rest of the day.

It depends on how hot I'm coming in on a particular talk. If I feel really prepared, I'll usually do one final run through that morning. I have been in the situation where I saw it wasn't quite finished the morning of, and so on those days, it's two, three, maybe four run throughs to try to get enough of that final polish and that I feel comfortable getting on stage and giving the talk.

You mentioned earlier nerves driving you to speed up. How do you deal with nerves nowadays?

It's more something I embrace than that I need to deal with. It's one of those things that over the years I've embraced it in my mind as a thing that makes me a better speaker.

Because it's a big part of the energy that I bring to the stage. I get on stage and there's that initial jolt of adrenaline right as you walk in front of the audience and you're doing the initial intro slide and getting into the meat of the talk.

There's the settling in that happens and the nerves kind of go down and I start to get into the zone at that point. I get into this flow state that I will be in for the 30 minutes that I'm giving the talk. But without that jolt of adrenaline at the start, I don't think I can get into that flow state.

I think that's a required precondition. I'm certainly not as nervous as I used to be getting on stage. It's actually one of my happy places at this point in my life. There are few places I enjoy more than being on a stage telling a story. But that's a thing that's developed over years as my confidence and my ability to do it has grown.

Yeah, I completely recognize that as well. Once you're done with the talk, and you're off the stage, what do you do then? How do you wind down from the adrenaline that you mentioned?

Always a deep breath or two. The post adrenal shutdown is a painful thing that always happens.

You've been hyped up on adrenaline for 30 minutes, and then you get off stage, the thing that was causing all this adrenaline through your body goes away. There is this wave of tiredness that kind of washes over me. So for me, usually the days that I speak, I've already planned a dinner or whatever for that day.

So I’m going to go and be around a small group of friends that I don't have to have a tremendous level of energy for. Because I know that I'm not going to have energy at the end of the day when I speak.

Other than that, my throat's usually pretty rough after I speak. So I like things to help my throat feel better, like a cup of hot tea or something.

Do you do anything to warm up your voice or vocal exercises or anything like that?

I don't. I do a lot of deep breathing, just to make sure that the nerves are where I want them to be and not running away from me. I will generally spend some time just walking around burning some nervous energy off backstage. But not really anything in the way of vocal warm ups. I probably should. That's a good point.

What's the most awkward or unexpected thing that has happened while giving a talk?

There was one time, I forget what year it was, at Lead Dev. The thing that makes Lead Dev such a fun place to speak is that they put your speaker notes on the confidence monitor, so it's not just your slides, you get your speaker notes on the stage in front of you.

For whatever reason, the zoom was off on the confidence monitor that had my speaker notes on it. About the right one third of my speaker notes was cut off on the side of the screen. It was like this fight in my head right as I started. Is it more professional to stop and ask them to fix this or is it more professional just to push through it?

Thankfully it was a talk that I felt pretty confident in and had a lot of it by memory at that point. So I was able to push through it and get through the talk. I know I left out some things that I wanted to say because I just couldn't remember the full bullet point that was in my notes. But that was one of those things where I was wrestling panic the whole time I was on stage, because I didn't have the security blanket of my notes. Even if I did have the talk mostly memorized, I was missing that security blanket.

That must have been tough. That particular scenario hasn't happened to me, but I've got similar stories of dealing with unexpectedness on stage!

What's the best speaking advice that you've ever gotten?

The best speaking advice I've ever gotten actually came in the form of a rejection from a conference. It was the very first time I had tried to put a proposal together for one of these storytelling style talks. I had put it together as a compare and contrast between two plane crashes.

This is what turned into the How to crash a plane talk. The advice I got back from the conference that I had submitted to was: we can't really tell what your talk is about. It seems to be too broad. You should find a way to focus your proposal more and submit it again next year.

That led me down the road of: “okay, well, I can tell this story without having to tell both plane crash stories. I can just tell one of them.”

It got me to the point where I was comfortable going, okay, I'm going to get on stage and spend 25 minutes telling a story. And then do five minutes of application at the end and see what happens. See if that's a thing that I can get away with at a software development conference.

And sure enough, the talk, once I revised it, got accepted. I got to get on stage and do it. I really fell in love with this style of talking and I've been doing it ever since.

I don't know that I would have found it without A, that talk proposal getting rejected by a conference and B, the organizers being generous enough to tell me why.

Okay, final question: what's one thing that you want people new to speaking to remember? Or to take away from all of this?

The advice I find myself giving over and over to people that want to get into speaking at conferences is that through the act of building a talk, you will become an expert on the subject that you want to speak about. So you don't necessarily have to be an expert before you propose a talk.

For me, if I look back on my speaking career, I can always tell what I'm going through in my career based on what I'm talking about, because there are always lessons that I'm thinking about in my everyday work as an engineering leader.

Those are the best fodder for talks. Things that you want to learn more about, things that you're curious about and want to spend three to six months doing a deep dive on to get to the point that you have 30 minutes of content about it. I know a lot of people are intimidated away from getting into speaking because they think they have to be an expert to earn that spot on stage.

And that's not how you earn the spot on stage at all. You earn the spot on stage by doing the research in developing a talk in the first place.

That’s great! And I very much agree with that: you definitely don’t have to be an expert to give a talk.

Thanks so much for your time, Nickolas!

If you want to see some of Nickolas' talks, check out the following:

- How to Crash a Plane, Lead Dev London 2016

- Who Destroyed Three Mile Island, Lead Dev London 2018

- The Magnitude 9.1 Meltdown at Fukushima, The Monktoberfest 2023